Hot Water

Sea urchins are like a canary in a coal mine. They give scientists an early warning for the future impact of rapid and extreme warming events, and their reactions to events like El Niño and to climate change are immediate and dramatic.

A team of researchers from Florida State University, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, University of California, Davis, and University of California, Santa Barbara, is using a $1.1 million National Science Foundation grant to better understand how heat waves impact urchin reproduction.

Daniel Okamoto, an assistant professor in FSU’s Department of Biological Science, is the principal investigator for the grant.

“Climate change and extreme heat waves strongly affect sea urchin populations,” Okamoto said. “When their numbers explode, sea urchins can devastate ecosystems by eating everything in their path. In northern California, heat waves mean massive amounts of baby sea urchins. In southern California, it’s the opposite, heat waves collapse the number of new young urchins.”

The study will focus on two primary factors believed to cause divergent outcomes: how temperature effects reproduction and how warming events effect ocean circulation.

Assistant professor of biological science Daniel Okamoto. Courtesy photo.

Direct effect

Warmer water requires urchins expend energy just to stay alive, which could mean less energy for females to produce eggs or the possibility populations may not reproduce at all. Persistently warm water from a different geographic landscape farther south may also be a culprit.

“Warm days aren’t going to kill a peach tree, but peach trees need a certain number of cold days to reproduce,” Okamoto said. “We think something similar could be happening with sea urchins.”

Heat also changes ocean water movement, which could impede survival and delivery of free-floating urchin larvae to near-shore ecosystems. The team will rely on oceanographic modeling led by UC Santa Barbara to characterize how circulation patterns have changed over the last 30 years.

Urchins are an ideal species for the study, in part, because of their quick response to temperature and ocean circulation changes. And they play an important role in near-shore ecosystems as a major herbivore and an important recycler of nutrients. But urchins can also turn out to be pests with the power to devour kelp forests and can continue to live even after the food is all gone.

Zombie urchins

Nate Spindel, an FSU doctoral student in biology, is leading work on a separate but related project about “zombie urchins.”

“Such urchins can create and then persist in barrens reminiscent of underwater versions of dystopian wastelands you might see on ‘The Walking Dead,’” Spindel said.

Zombie urchins can slow their metabolism, contributing to their unique capacity to weather famine. Spindel’s work could provide insight into how temperature affects metabolism and, in turn, impacts energy for reproduction, Okamoto said.

“Dr. Okamoto’s approach to science involving the creative combination of laboratory and field studies and cutting-edge computer modeling struck me as a productive and fascinating path forward.”

— Nate Spindel, Doctoral Student

The project’s interdisciplinary approach is ambitious and exciting and a perfect example why Spindel chose FSU for his doctoral work.

“Dr. Okamoto’s approach to science involving the creative combination of laboratory and field studies and cutting-edge computer modeling struck me as a productive and fascinating path forward.”

Daniel Okamoto (center), Ondine Pontier (left) from the Hakai Institute in Canada, and Nate Spindel (right) conduct field work in British Columbia. Photo by Markus Thompson.

Generational research

The NSF project takes advantage of data and urchin samples collected by researchers and students since 1990 from the California coast. Okamoto joined that collection effort as a UCSB graduate student in 2009, but the work was initially begun in the 1980s and ’90s by his collaborator Stephen Schroeter at UCSB, Tom Ebert at Oregon State University and others.

A component of the grant calls for working with K-12 students, in order to empower the next generation of scientists to think about the local consequences of climate change. FSU is distinctly prepared to carry out such a mission through its Office of STEM Teaching Activities outreach programs.

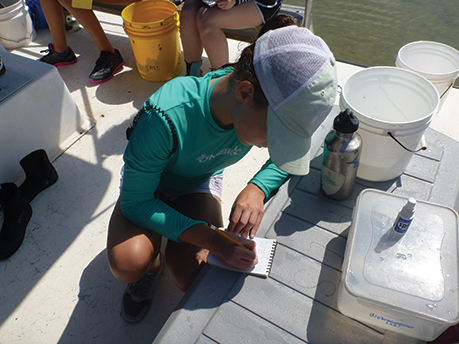

Barbara Shoplock, an FSU biologist and director of OSTA’s Saturday-at-the-Sea programs, will help translate this Tier 1 research into formats most accessible for budding scientists. Middle and high school students will day trip to the FSU Coastal and Marine Laboratory and collect urchins in the Gulf of Mexico and be part of monitoring how local populations are reacting to a changing climate.

“Dr. Okamoto’s grant will enable us to bring more actionable science to these middle and high school students and allow them to become ambassadors for awareness in their local communities,” Shoplock said. “That matters because now, more than any other time in human existence, we are aware of the fragile, interconnected nature of the world that we live in.”

The availability of resources like seafood is not guaranteed, Okamoto said. It’s critical to first understand how near shore ecosystems respond to a change in climate in order to find ways to mitigate those effects.